The silent threat of perinatal depression: Why holistic care is needed to improve maternal and newborn health in Nigeria

Welcoming a new baby to the world is often considered one of the happiest and most amazing events in a woman’s life; however, this doesn’t come without its challenges for many new mothers. Many new moms experience the baby blues – a mild, brief bout of depression – within the first few weeks of giving birth. However, for some women – more than 10 per cent of mothers – feelings of sadness, emptiness, or loss of joy can last a year after childbirth and can interfere with a mother’s ability to care for herself, as well as her ability to care for and bond with her baby. The impact of common perinatal mood disorders, like depression, can lead to worse health outcomes for these women and can impact the child’s development and safety. In rare cases, new mothers have harmed themselves and their babies.

Perinatal depression refers to severe depressive episodes during pregnancy and/or within 12 months postpartum and is one of the most common reproductive complications. It is often characterized by symptoms such as tearfulness, a feeling of hopelessness, sadness, despair, anxiety, irritability, emotional liability, feelings of guilt, sleep problems, and loss of appetite and can result in poor maternal bonding and failure to initiate breastfeeding or shorter breastfeeding duration. Certain risk factors have been reported for perinatal depression in high, middle, and low-income countries – unplanned pregnancy, mode of delivery (particularly Caesarean section), high parity, premature delivery, unintended and unwanted pregnancy, poor economic status of families, infant illness after delivery, not having assistance with caring for self and the baby after birth and lack of social support.

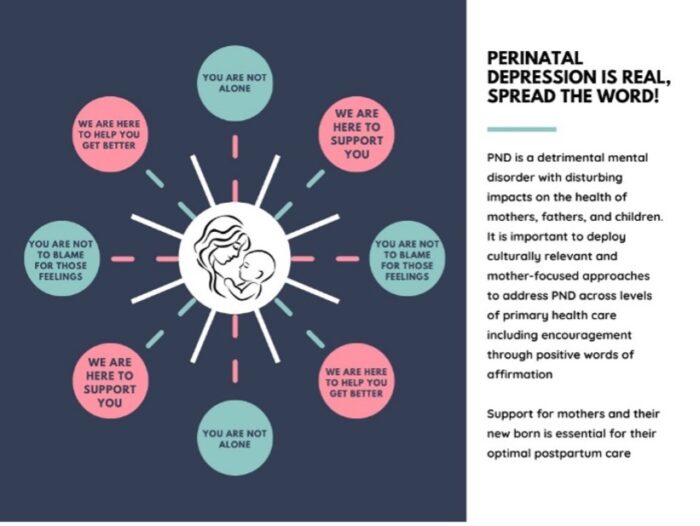

In Nigeria, perinatal maternal depression is common with reported cases of 10-30%. Despite the high disease burden, it is often undiagnosed and undertreated due to a lack of or limited mental health infrastructure, the stigma associated with being a single mother or having a child out of wedlock which prevents women from seeking care, judgement from families, communities and health care workers, and lack of training for health care workers on early diagnosis and intervention.

A holistic model of care to improve maternal and newborn health in Nigeria would require comprehensive, culturally relevant, and adaptable antenatal and postpartum care. This could be achieved by allocating a percentage of the health budget specifically to integrating quality perinatal mental health services into existing maternal and newborn care platforms to assist in early diagnosis, prevention and treatment of perinatal depression. Furthermore, to ‘nip the bud of perinatal depression’, it is essential to invest in effective and efficient training of mental health care workers to equip them with essential skills and resources for early detection of perinatal depression and prompt delivery of intervention strategies. The World Health Organization’s (WHO) Mental Health Gap Action Program Intervention Guide can be adopted to build the capacity of existing community health workers to deliver mental health services to women in the perinatal period.

Nigeria’s commitment to improving the maternal and newborn health metrics to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals, particularly Goal 3’s targets of reducing the global maternal mortality ratio to less than 70 per 100,000 live births and ending preventable deaths of newborns and children under 5 years of age, remains unwavering. However, the country must invest in innovative, culturally relevant, and women-centered approaches to address perinatal depression in primary health facilities across the country. There is also a need to allocate funding for research to evaluate the impact of existing policies on the mental health of perinatal women, including underserved populations, adolescent mothers and lower-income women in the country.