Safeguarding Maternal and Perinatal Health for Women Living with Sickle Cell Disease

Summary

The new WHO recommendations on managing sickle cell disease in pregnancy are a groundbreaking step toward safer, more equitable maternal and newborn care for women worldwide, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa.

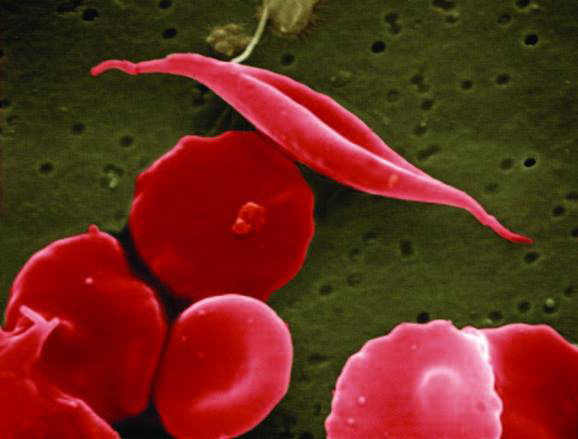

Sickle-cell disease (SCD) is a group of inherited disorders caused by a gene mutation that produces abnormal hemoglobin and, consequently, abnormal red blood cells. This compromises the capacity of red blood cells to optimally do their job of transporting oxygen around the body to the tissues.

As a result, the abnormal red blood cells have a shorter lifespan, with resultant chronic anemia. Their loss of flexibility limits their ability to move through smaller blood vessels, causing occlusion. This leads to poor oxygen supply to the tissues, with severe complications such as vaso-occlusive crisis, acute chest syndrome and even strokes. People living with SCD are also not only prone to bacterial infections, but also likely to have severe disease, due to loss of the immune protection that the spleen provides.

Sickle-cell disease affects approximately 7.74 million people worldwide, with an average of 300,000 children born with the disease each year, 75% of them being in Africa. Sub-Saharan Africa bears the highest burden, followed by the Middle East, the Caribbean and South Asia.

With better understanding of the disease comes advances in care, including timely interventions through childhood, improved quality of life and longer life expectancy. Some of these interventions include medications that optimize the patient’s condition and reduce complications, such as folic acid, hydroxyurea, crizanlizumab, L-glutamine, prophylactic penicillin, and targeted vaccination.

Patients have better pain management during moment of sickle-cell crisis; and further, both treatment and prophylactic blood transfusion have been mainstreamed into care. Curative treatments currently include stem cell transplant and upcoming gene therapies.

This has seen the number of people living with SCD increased by 41.4% between 2000 and 2021; including women who are getting to childbearing age and desiring motherhood.

However, the majority of these same women also happen live in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where 95% of maternal mortality occurs. According to the 2015 WHO report on inequality in reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health, the high maternal mortality rates are fueled by inequities that include poverty, low education levels and poor access to healthcare, leaving women with sickle-cell disease at significant risk.

What Does the Combined Risk of SCD and Pregnancy Mean to Women?

Sickle-cell disease is a neglected condition, with inadequate resourcing, reflecting the inequalities in access to care for women living in sub-Saharan Africa. This means that they are disproportionately disadvantaged, even before they take on the additional risks that come with pregnancy, due to their socio-economic disparities.

These women are less likely to access the technological advances that have improved the lives of people living with SCD; hence are more likely to start the pregnancy journey from a point of disadvantage. They are unlikely to access pre-conception care; they have limited access to the highly-skilled multi-disciplinary teams needed for their delivery; and the are likely to need referral to facilities far away for the management of complications, once they set in.

While the risk of maternal mortality in women with SCD is estimated to be 4-11 times higher than that of women without the disease, the risk is likely to be even higher for women from LMICs. They also face a higher rates of pre-eclampsia, premature birth, low birth weight and stillbirth.

A Game-Changer For Maternal Health

In the face of such glaring disparities, closing the gap has been out of reach for this special population due to lack of sickle-cell disease care guidelines in pregnancy, childbirth and in the postpartum period. Despite existence of guidelines for the management of SCD from as early as 1989, recommendations on care in pregnancy has largely been restricted to high income countries, which, ironically, have the lowest disease burden.

This is why the newly launched “WHO Recommendations on the Management of Sickle-cell Disease During Pregnancy, Childbirth and the Interpregnancy Period” are a game-changer for these women. They represent a great milestone in the push to achieving the global commitments for maternal and newborn health, through the Every Woman Every Newborn Everywhere (EWENE) movement.

These Recommendations are intended for global use, but they have been developed with the low-resource settings in mind, where the heaviest burden of disease resides. Ultimately, these are the settings with the greatest potential for impact. Further, at country-level adoption, they build a foundation for policy-makers to curate not just obstetric care guidelines, but also wider sexual and reproductive health guidelines for girls and women living with sickle-cell disease.

The Recommendations align with WHO’s vision that “every pregnant woman and newborn receives quality care throughout pregnancy, childbirth and the postnatal period.” They emphasize woman-centered, respectful care while managing sickle cell disease-related risks.

Importantly, the Recommendations address the evidence gap regarding medication safety in pregnancy and breastfeeding, a key barrier to SCD treatment in pregnancy. Most healthcare providers will tend to err on the side of caution; yet, optimizing SCD care during pregnancy and breastfeeding gives both mother and baby the best shot at good outcomes.

The 21 Recommendations

The WHO Guideline Development Group (GDG) considered the available evidence; what is known about the physiology of pregnancy; and what is known of the underlying pathophysiology of SCD. This was considered against the balance of health benefits and harms; human rights and sociocultural acceptability; health equity, equality, and non-discrimination; societal implications; financial and economic considerations; feasibility and health-system considerations; and women’s views and preferences, in arriving at the following recommendations:

1. Medication management for women with SCD in antenatal care:

- Folic acid supplementation: those living outside malaria endemic areas to take daily supplementation with up to 5 mg folic acid; those taking intermittent preventive treatment with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine to take 400 μg folic acid to prevent counteracting the efficacy of the antimalarial.

- Iron supplementation: iron supplementation is not needed unless there is evidence of iron deficiency; for those with iron deficiency, supplement iron supplementation as for the general pregnant population

- Prophylactic blood transfusion: For those with a history of severe intractable crises or with lived experience of previous benefit from prophylactic transfusion outside of pregnancy, consider prophylactic blood transfusion.

- Hydroxycarbamide (hydroxyurea): For those previously controlled with hydroxycarbamide (hydroxyurea), consider continuation or recommencement (after the first trimester) in the context of shared decision making involving the woman and a multidisciplinary team, based on risk–benefit analyses on the woman’s symptom severity, stage of pregnancy and her views and preferences.

- Thromboprophylaxis: consider additional risk factors for thromboembolism and follow local recommendations for initiation of thromboprophylaxis for pregnant women with elevated risk of thrombotic events e.g. prior VTE, obesity, inherited thrombophilia

- Infection prophylaxis: routine infection prophylaxis is not recommended; instead, implement frequent screening for infection with a low diagnostic threshold for bacterial urinary tract infection.

2. Pain management for pregnant women with SCD:

- Pain medication: For acute sickle-related pain, timely and optimal pain relief, using oral paracetamol, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), or opioids at the lowest effective dose for the shortest period of time required to manage pain; considering the stage of pregnancy and contraindications for specific medications, the woman’s views, preferences and previous experience of the medication, risk of dependence, and availability.

- Pain management plans: Collaborate with the pregnant woman with SCD to develop an individualized pain-management plan as early in pregnancy as possible.

3. Management of women with SCD who are hospitalized during pregnancy:

- Fluid management in pregnant women hospitalized with SCD: For those hospitalized with vaso-occlusive crisis and requiring intravenous fluid hydration, implement frequent clinical monitoring for early identification of fluid overload and pulmonary oedema. For those with complications such as pre-eclampsia, implement more intensive monitoring.

- Thromboprophylaxis in pregnant women hospitalized with SCD: Offer thromboprophylaxis to hospitalized women, unless contraindicated

4. Fetal monitoring:

- Additional fetal monitoring during pregnancy: For those without complications, offer growth/biometric scans to identify fetal growth restriction every four weeks from 24 until 32 weeks’ gestation, and then every three weeks until birth. For those with complications, offer individualized intensive fetal monitoring to guide management.

5. Care around birth:

- Timing of birth: individualized approach to timing of birth, based on the anticipated balance of the benefits of continuing pregnancy to allow fetal maturation and the risk of maternal and neonatal morbidities associated with continuation of the pregnancy, and the woman’s views and preferences.

- Mode of birth: Based on presence or absence of medical or obstetric indications for caesarean birth, availability of local resources, and the woman’s views and preferences; with vaginal birth being preferred in absence of medical or obstetric indications for caesarean birth.

6. Interpregnancy management:

- Interpregnancy care: In the immediate postnatal period and up to six weeks after childbirth, provide care as outlined in WHO recommendations on maternal and newborn care for a positive postnatal experience; in addition to managing SCD and its complications, using hydroxycarbamide (hydroxyurea) and pain-management strategies; thromboprophylaxis as per local recommendations; and guide choice of contraceptive methods; screen the newborn for SCD; and guide counselling on the safety of breastfeeding for her baby.

- Health service programs: Integration of care across the life course, including sexual and reproductive health care, with specialized disease care, which may include: supporting optimal health; providing pre-pregnancy counselling and guidance on pregnancy planning; and optimizing treatment across the reproductive continuum.

The recommendations are certainly not exhaustive as they are intended to address the management of SCD during pregnancy, childbirth and interpregnancy period. There is still room for expansion to address obstetric care in SCD, with more detailed guidelines on management of the preconception period, antenatal care, care during delivery itself and interpregnancy care.

Harnessing the Opportunity for Equity

Sub-Saharan Africa continues to lag behind in key Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) targets, including maternal health outcomes. Alongside all other challenges that may slow down countries in achieving the 90/90/80/80 EWENE coverage targets, SCD presents an independent challenge unique to the region that continues to hold countries back.

The WHO Recommendations have validated the need for policy advocacy, local guideline development, clinical leadership, and health systems strengthening. They have made women living with SCD visible, elevating them to a platform where their voices can be heard. It is a positive challenge for all of us in women’s health to respond to their asks. Our response must go beyond strengthening care provision to support investment in local clinical trials, that include pregnant women with SCD as study subjects. This will help generate the necessary body of knowledge that is sorely lacking. Research must also include implementation science, to ground policies in evidence of local sustainable solutions that remain culturally sensitive and patient-centered.

Further, the Recommendations have laid ground for obstetric care in SCD. This will provide guidance on care for uncomplicated and complicated pregnancies in spite of the woman living with SCD. Care standards for pain management in labor in resource-limited settings, fluid balance in the use of oxytocics, obstetric complications in the face of SCD such as preeclampsia, hemorrhage, rhesus incompatibility and many other considerations; because SCD does not make them immune to all other obstetric complications.

This must be accompanied with gynecological recommendations, starting from adolescent transition, menstrual disorders in girls with SCD who cannot afford complications such as heavy menstrual bleeding; early education on contraceptive choices even before pregnancy; and most importantly, that our women living with SCD are making it to menopause now, and we need to ensure we are ready for their care.

In the spirit of leaving no one behind, the Recommendations also build a case for inclusion of comprehensive SCD care in local universal health coverage programs to ensure equity. Not only should we strengthen SCD care programs but also integrate these services in the mainstream health systems as part of routine care.