Preventing Postpartum Hemorrhage for Every Woman, Wherever She Gives Birth

(on behalf of the EQUAL Research Consortium and the Safer Births in Crises Consortium)

A persistent equity gap

An estimated 18 to 22% of births globally occur outside health facilities. In humanitarian settings, that proportion is often far higher—sometimes half of all births or more, especially among displaced or remote populations. Many women give birth at home not by choice, but because conflict, displacement, poverty, insecurity, and weak health systems limit their options.

Global guidance rightly prioritizes facility-based delivery as the safest option. But in many humanitarian contexts, this is aspirational. Facilities may be too far, unsafe to reach, understaffed, or closed altogether. Curfews, checkpoints, or violence can turn routine labor into a life-threatening emergency.

The question, then, is not whether facility-based delivery is ideal, but what does responsible, lifesaving care look like when facilities are inaccessible?

For postpartum hemorrhage (PPH), the leading cause of maternal death globally, this question is urgent. Yet with the right intervention, given at the right time, PPH is preventable. To reduce risk of PPH, it is recommended that every woman giving birth receive medication immediately after delivery to help the uterus contract. Without this medication, risks of bleeding are higher and once severe bleeding begins, there is often little time for referral or transport. In places where home births are common, prevention cannot be an afterthought.

What the latest PPH consolidated guidelines say

The 2025 World Health Organization “Consolidated guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of postpartum haemorrhage” recognize that humanitarian settings may require greater contextualization and adaptation. They reaffirm that “in settings where women give birth outside of a health facility and in the absence of skilled health personnel, a strategy of antenatal distribution of misoprostol to pregnant women for self-administration is recommended for prevention of postpartum haemorrhage.” The guidelines also note that trained community and lay health workers may administer misoprostol for PPH prevention where skilled personnel are unavailable. Advance distribution should be context-specific and supported by clear instructions for correct use, supervision, and monitoring.

The reality of implementation in humanitarian and crisis-affected settings

But translating guidance into practice is rarely straightforward—especially in humanitarian contexts. What does “advance distribution” look like when:

- Active conflict, curfews and checkpoints restrict movement

- Healthcare services are interrupted or relocated due to staff displacement, flooding or insufficient resources.

- Political structures are complex and fragmented.

- Supply chains are unreliable, interrupted, or controlled by multiple actors.

- Health workforce shortages leave midwives and community providers overstretched.

In these settings, no single delivery model will work everywhere – or for everyone. Effective implementation requires flexibility: understanding the intent of guidance and translating it into approaches that actually work in the field.

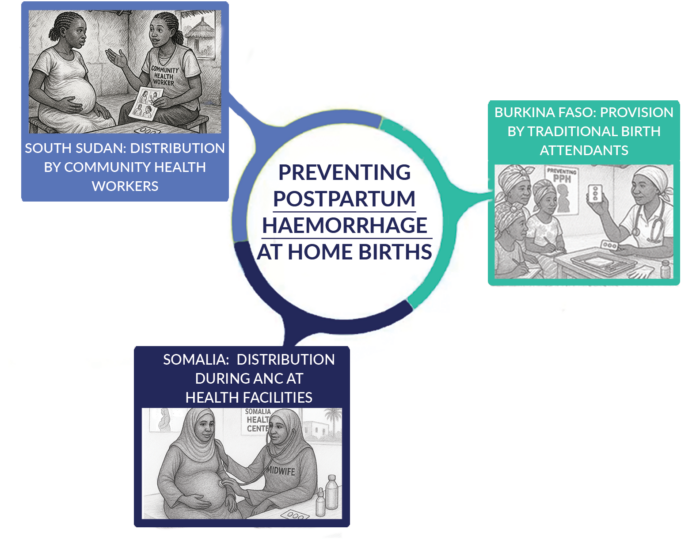

Adaptation in action: three pilot models, one goal

The following examples show how this plays out in practice – with a focus on misoprostol because it is well-suited for advance distribution and community-level use. While not the ideal approach – birth in a facility with skilled health personnel and resources to quickly manage emergencies when they arise would be preferable – these pilots show what is possible in contexts where home birth is common and access to facilities is limited.

South Sudan: Distribution by Community Health Workers (EQUAL Research Consortium / IRC)

The IRC trained Boma Health Workers – the national community health cadre – to distribute misoprostol to pregnant women in their third trimester during home visits. Driven by stakeholder concerns of misuse, the pilot incorporated robust monitoring and tracking processes, including collecting wrappers and unused tablets. Additional safeguards included branded packaging in local language, pictorial education tools, and pre-cut tablets to ensure correct dosing and appropriate use.

Burkina Faso: Provision by Traditional Birth Attendants (IRC)

In areas where conflict and service disruptions forced health center closures, the IRC implemented a community-based misoprostol pilot in partnership with the Ministry of Health. Traditional Birth Attendants were trainedto carry clean delivery kits and to safely administer misoprostol for PPH prevention during home births in these hard-to-reach settings.

Somalia: Distribution during Antenatal Care at Health Facilities (International Medical Corps)

in Somalia, IMC piloted a model in which midwives distributed misoprostol during routine antenatal care visits at health facilities for women in their third trimester. Both midwives and CHWs were trained to counsel women on PPH risks and prevention strategies, including guidance on when and how to take the medication, and what to do if side effects occur.

Lessons from implementation

Together, these pilots demonstrate that community-based and task-shifted approaches to preventing PPH are feasible. While all follow the same clinical guidance, the way care is delivered varies by context. For these pilots, several important lessons emerge.

- Align approaches with existing care-seeking patterns: Interventions are more likely to succeed when they fit how and when women already interact with the health system or trusted community providers.

- Task-shifting works when roles are clear and supported: Shifting responsibility requires more than training. It requires supervision, clear roles, and ongoing support to maintain safety, confidence, and quality.

- Community acceptance is critical: Safe interventions only work if communities trust them.Early engagement and clear communication about who delivers care, when, and why, are important for appropriate use.

- Design monitoring for scale: Intensive tracking may be feasible in small-scale pilots but often faces challenges upon scaling. Monitoring should balance accountability with feasibility, using simple tools and processes that frontline workers can manage in unstable environments.

From pilots to scale

These models show what is possible, but in humanitarian settings, promising pilots rarely make it to scale. Understanding what worked is just the start – moving beyond a “proof of concept” requires addressing policy, operational, financing, and system-level barriers.

Adapting PPH prevention for home births is not a replacement for strong health systems. Instead, it serves as a bridge when systems are disrupted, fragile, or out of reach. These approaches don’t lower standards, they put evidence-based guidance into practice where the alternative is often no care at all. In that reality, adaptation isn’t a compromise—it is a responsibility that saves lives.

To continue this conversation, the EQUAL Research Consortium and the Safer Births in Crises Consortium will co-host a joint webinar on February 5 featuring speakers from each of these pilots. The discussion will dive deeper into what worked, what stands in the way of scaling these approaches, and key lessons for policymakers and implementers.

Register here: bit.ly/3MXQr5U

Learn more about the work of the EQUAL Research Consortium and the Safer Births in Crises Consortium