4 Lessons for Implementing Effective Community MPDSR from Nigeria

Across Nigeria, three out of every five women give birth at home without the services of skilled birth attendants (NDHS, 2018). A better understanding of the realities of maternal and newborn health at the community level is important for increasing skilled birth attendance at delivery and preventing avoidable deaths going forward.

The Maternal and Perinatal Death Surveillance and Response (MPDSR) system is a very useful way to track and monitor deaths and understand their causes. However, at present, implementation of MPDSR in Nigeria is limited to deaths in secondary and tertiary facilities. This means that many deaths go unaudited and preventable causes go unaddressed.

In this post, we briefly describe how we implemented our community-MPDSR model in collaboration with the Kaduna State Government and offer four takeaway lessons to guide future efforts elsewhere.

What is c-MPDSR?

Community-MPDSR, referred to as c-MPDSR, is a model that ensures maternal and perinatal deaths are identified, documented and audited regardless of the place of death – including those that occur at home, in transit to a health facility or at the facility.

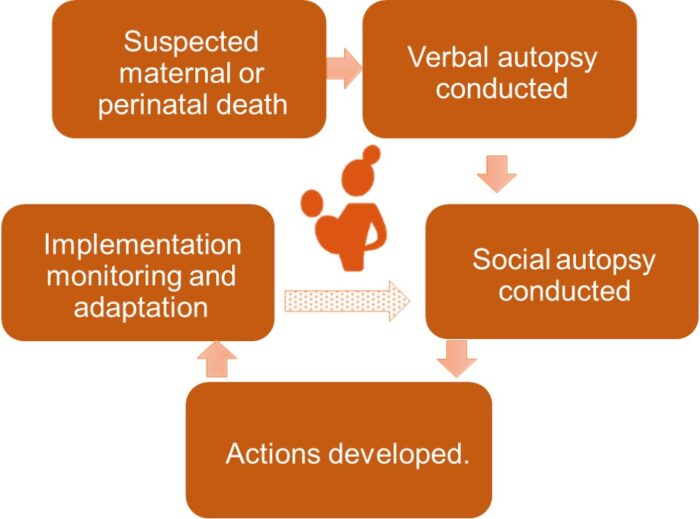

Our model supports communities in the use of verbal and social autopsies to gather data on the root causes of death and develop actions to prevent future occurrences.

Our c-MPDSR model in Kaduna

The Evidence for Action (E4A)-MamaYe project, managed by Options Consultancy Services with partners that include the Kaduna State Government, implemented a pilot c-MPDSR project over a six-month period from January to June 2022 in one urban community, Soba, and in one rural community, Yakasai – both in the Soba Ward (district) of the Soba local government area (LGA), one of the 23 LGAs in Kaduna State, Nigeria. The project adapted the tools used in a study in rural Malawi, and an endline evaluation of the project can be accessed at this link.

This c-MPDSR model is an adaptation of previous c-MPDSR as it features integration of community-led social autopsy in addition to verbal autopsy. Figure 1 illustrates the c-MPDSR model.

The model brought together stakeholders from the LGA, the ward (district) development committee, the community and health care workers from local facilities.

There are no tertiary health facilities or specialist hospitals in the Soba LGA. However, there is a ward primary health care (PHC) center, two other PHC centers, and one private clinic in the LGA.

Health care workers and selected representatives of a local c-MPDSR committee conduct a verbal autopsy with the family of the deceased to gather information on both medical and non-medical (focusing on the economic and sociocultural) factors that led to the death. The social autopsy brings together all stakeholders to discuss and agree on actions to prevent future deaths using information collected during verbal autopsies.

4 lessons from our implementation of c-MPDSR in Kaduna

In this section, we share four key takeaway lessons that we believe are useful for guiding implementation of future c-MPDSR systems inside and outside Nigeria.

1. Communities are ready, able and committed to leading solutions to prevent maternal and perinatal deaths.

The level of community participation in our c-MPDSR model is fascinating, and they view social autopsy as an opportunity for learning how to improve maternal and child health in their communities.

Here are three ways we see the community already delivering change. Men are becoming the agents of change who encourage and support their wives to go to primary health care centers for antenatal care and facility-based deliveries. Once called, the National Union of Road Transport Workers’ (NURTW) drivers in the communities now transport pregnant women to health facilities. Members of a community-based organization now screen for blood transfusions and are prepared to identify blood donors during emergencies.

2. Working collaboratively with diverse local stakeholders means actions get addressed.

The presence of different actors working at different levels of the health system helped ensure that actions developed during the social autopsy could be implemented across the system.

For example, the Soba ward development committee requested a workplan for the community visits by health care workers so they were aware which health workers were in which community and could then follow-up on the implementation of actions assigned to them. This allowed them to keep track of actions such as raising awareness about antenatal care visits and facility delivery, in collaboration with other stakeholders such as imams, pastors and women’s groups.

Additionally, the presence of health care workers from local health facilities meant that immediate changes could be made to service delivery in response to community feedback. For example, the lack of female midwives at night was identified as causing many women not to attend health facilities. Thanks to actions taken as a result from the social autopsies, female midwives have committed to being available 24 hours.

3. Mainstreaming gender in the design and implementation of c-MPDSR reduces harmful gender norms.

Patriarchal socio-cultural norms often limit the agency of women and girls.

In order to ensure that actions developed during the social autopsies do not encourage or further entrench harmful gender norms, we conducted focus group discussions to better understand how these norms operate in the communities. We embedded those findings into the tools and resources developed for c-MPDSR, and trained the c-MPDSR committee members on gender equality and mainstreaming gender to ensure that they facilitate the design of actions that empower rather than limit the agency of women and girls.

4. Sustainability takes time and investment.

The c-MPDSR model requires substantial investment for it to be effective and sustained.

For example, facilitating sensitive discussions in social autopsy sessions with a large group of people requires considerable skill. Many of the c-MPDSR committee members were new to the three-delays models and had to build their understanding of contributory factors to maternal and perinatal mortality. This process took time and required supportive supervision from community health specialists. The sustainability of the model also requires an implementation timeline that allows for extensive training of the c-MPDSR committee.

c-MPDSR has lifesaving potential, invest in it!

As the takeaway lessons above illustrate, our results show that communities can identify and discuss causes of maternal and perinatal deaths and come up with actions that save lives and improve the health of women and newborns. E4A-MamaYe will share the tools used in their approach in April 2023 on their website, so as to help guide other governments or partners on how to set up and support the implementation of c-MDPSR in their own communities.

Dr. Moshood Salawu is the MPDSR Advisor for Evidence for Action (E4A)-MamaYe, a project managed by Options Consultancy Services and funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Photo credit: Meshack Acholla/E4A-MamaYe